The notion that the best place for a woman is the home is, for the most part, seen as an outdated one in the 21st century. In 2020, the home is the best place for everyone! However, this extended period of being at home has set me thinking about what home represents for women, and the fact that women can often have a complicated relationship with the notion of home…

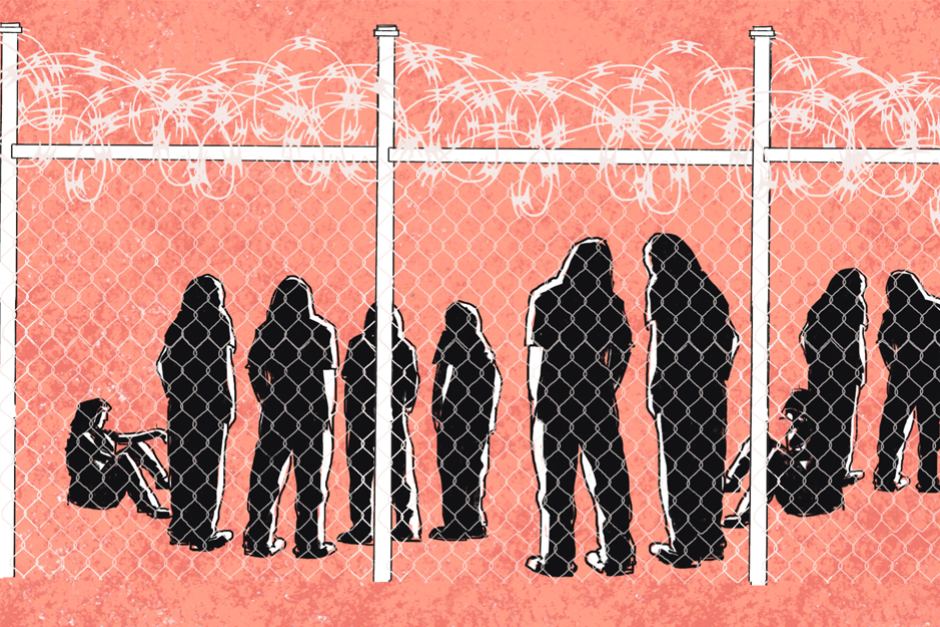

Home and Prison: Women, Sentencing and the Private Sphere

CW: Domestic Violence

Home can mean different things to every woman. One topic that I feel gets little airtime is what home means for women who commit crime, and how outdated notions around women and domesticity persist in the courtroom.

The gender disparity in sentencing outcomes has garnered a lot of attention by criminologists over the years. Generally, female offenders are less likely to be sentenced to prison, even when compared directly against equivalent crimes by men. There are a number of straightforward explanations for this: for example, women are more likely to be first-time offenders, and less likely to be involved in serious, violent crime.

However, there is still evidence that sentencers view women through a lens of stereotypes and oppressive gender norms. Women are often viewed as more fragile than men, and less capable of violence. Sentencers display attitudes of paternalism towards female offenders.

In particular, the home and family is constantly invoked as the ideal site of containment and surveillance for female offenders, even when they have been violent towards their own children. These attitudes are based on the concept of formal or informal ‘social control’ – a term which here means a mechanism in society that ensures that people comply with norms such as gender. Formal mechanisms of control include prison or psychiatric intervention; informal mechanisms of control are usually the disapproval of others, or pressure from family or friends to act a certain way.

Female offenders are often seen as too fragile for the formal intervention of prison. The home is the best place for them, and the family can exert a degree of informal social control that will suit them better. Numerous reports indicate that the assessment of female criminals revolves around their ability as home-makers, mothers and wives; the home is the more appropriate place for women, and hence women are less likely to be given prison sentences.

Probation officers investigating female offenders will often mention the state of the home and children in the report; for male offenders, this is not a concern. In the US, sentencers were given a more positive impression of offenders when family members were willing to speak on their behalf, and particularly if they could be assured that a male authority figure, in the form of husband or father, would be present in a female offender’s life.

Therefore, paternalistic attitudes from sentencers – usually male, white, and upper-class – mean that the private sphere is seen as the more appropriate place for women.

Of course, only certain women benefit from these assumptions of fragility. Women who resist the informal mechanisms of family, e.g. by being single, are more likely to be given harsher sentences. Women of colour and working-class women are stereotyped as tougher, and in need of more formal intervention in order to effectively punish.

This trend in sentencing is unfortunate on a number of counts. Firstly, it’s based on a long lasting stereotype of women as naturally better at being homemakers and economic dependents. It occasionally strays into outright racism, in a justice system that oppresses people of colour at every opportunity. Furthermore, it further confines women to the ‘private sphere’, an aim fulfilled by many institutions in patriarchal society. This confinement makes women more prone to victimisation in the form of domestic violence, isolation, and mental illness. This is particularly concerning when one considers that female offenders are amongst the most vulnerable members of our society, and incredibly likely to be victims of abuse, or struggling with addiction.

In conclusion, it’s important to remember that this time at home is not always a blessing in disguise. For many women, it represents confinement, isolation, oppression, and even abuse. Evidence is showing that women are overrepresented amongst those who have lost their jobs due to the lockdown, and that women are more likely to quit their jobs during lockdown to be primary carers. The private, the home, is still seen as the domain of women.

Once this is over, and we return to public life, we must ensure that everyone is equally able to return, and that we do not continue to enforce this divide between men, women, the public and the private spheres.

Caitlin Flavell, Political Editor

Header Illustration by Rocco Fazzari

Leave a Comment