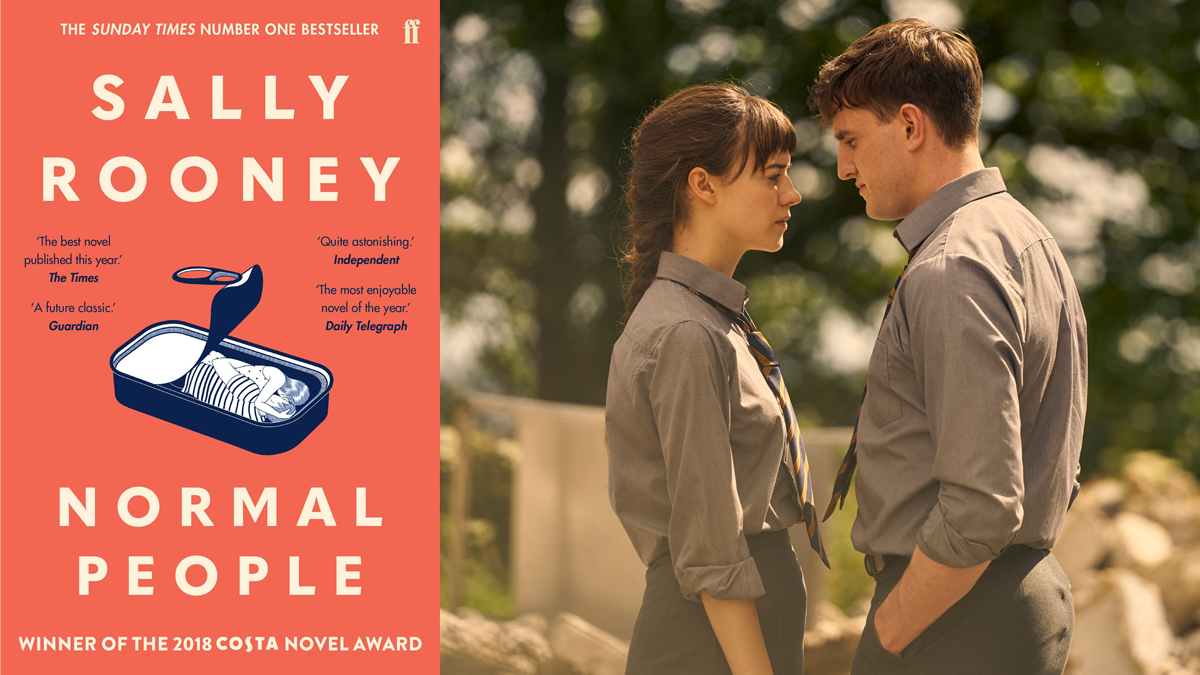

Normal People is a book I read around a year and a half ago, whilst at home from university for Christmas. It left me feeling haunted due to its sense of such familiarity – leaving your hometown for a new city, to a university with elitist tendencies, only to face a life you could never had imagined had you decided to stay at home…

What ‘Normal People’ reveals about mental health

I saw so much of my own life in Marianne and Connell’s experiences, and to this day I’m yet to read a book which feels so intimate.

The newly-adapted show for BBC Three, however, took this to another level. I could now physically see the contrasts: the minuteness of leafy suburban roads, then the enormous beast that is a capital city. The characters, too, could easily be my fellow classmates: individuals who talk for the sake of talking in a tutorial because no one has ever told them to shut up; the self-righteous man who ‘doesn’t believe’ in white privilege; the friend who slightly overshares about their sex life. I could have been watching Made in Chelsea (or perhaps a less staged and upper-middle class equivalent, with more dramatic pauses and longing stares), it was that realistic.

Nothing quite prepared me, however, for episode eight; this episode was so familiar it stung. Without giving too much away, Connell is hit with a tragic loss and as a result falls into a depression, making it difficult for him to continue with life as normal. This depiction of depression showed a shrunken man, a human being turned inward. It was a sight I recognised – I had looked somewhat like too, at one point or another.

What struck me most were the counselling scenes. Connell enters his university’s counselling service waiting area – a clinical shell of a building with off-white walls, tattered blue chairs (you know the ones) and scattered leaflets showing other (and potentially more useful) services on offer. He sat, shrunken as ever, not knowing where to look, until the counsellor calls his name. He enters her office, perfectly embellished with the old favourites: the tissue box on the coffee table, one sticking out ready to wipe the inevitable tears; the stacks of books about Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and its ilk; the endless sheets of suggestions of apps to download (good old Headspace). It was a sight I’m sure many students have encountered and can relate to. It was this that hit me the hardest; a room with a stranger, in a city unfamiliar, not recognising this version of yourself. As Connell began to describe how he was feeling, he began to uncontrollably sob – something I myself did in counselling sessions, constantly apologising and avoiding eye contact. It’s funny how these strange rooms see the rawest, most vulnerable version of you.

University counselling services are not therapy. They are a way of venting and being able to talk to an impartial stranger, who just so happens to be trained. They are a way of making the first step towards feeling better. They are also criminally underfunded; The Guardian writes that in many British universities there are often only ten counsellors for tens of thousands of students. Waiting times are often hideously long, and this is an extremely dangerous problem with potentially detrimental consequences. This is no fault of the service itself, rather the wider bureaucracy which universities tend to hide behind. This is what made this scene so jarring; that this underdevelopment, this neglect, was commonplace.

This is not to say that counselling does not help. I found it extremely beneficial and it empowered me to learn how to talk about my mental health (something I am still pretty awful at) and how to control certain behaviours. It is always worth going to, even if you are just toying with the idea. It is one of the only times in your life a service like that will be offered free of charge, so take it while it is still there. In the show, it is Connell’s friend who urges him to visit the service, saying that he might as well try it since it’s there. This is the exact sentiment all students who are struggling should embody – you never know how positive an impact it may have on your life in the long-run.

As Connell left the building, he is hit with a bustling main road. Unbeknown to the passers-by, he just spilled his heart out about his friend’s suicide and his own feelings of hopelessness and guilt. He spoke in a way which he clearly had not done before, and in a way which allowed him to decompress. These passers-by do not know this about him, and yet he must now join them. This juxtaposition has always felt incredibly jarring to me, and it was depicted so accurately in the scene; you have just opened up, and now you must go on.

In times like today, I think we all need a show like Normal People. A show which can illustrate what life is normally like for many of us, and can act as a reminder of both what we have overcome and what lies ahead. I need to improve on myself, as does Connell. We are always working towards that end goal of complete contentment within ourselves. Our bodies strive for greatness, as do our minds, but we too must be kind to ourselves. Taking that one step towards kindness is sometimes the most important thing we can do for ourselves, and I urge everyone to do one little nice thing for their brain today (maybe by watching this show!).

Leave a Comment