A few days ago a large number of houses in central Edinburgh experienced a power cut. My phone was on 5% so I went to charge it and then realised that I couldn’t do that. I also had to go to the loo and as I made the trepid journey out of the safety of my covers into the dark abyss of all two metres I tried to turn the bathroom light on but also couldn’t do that.

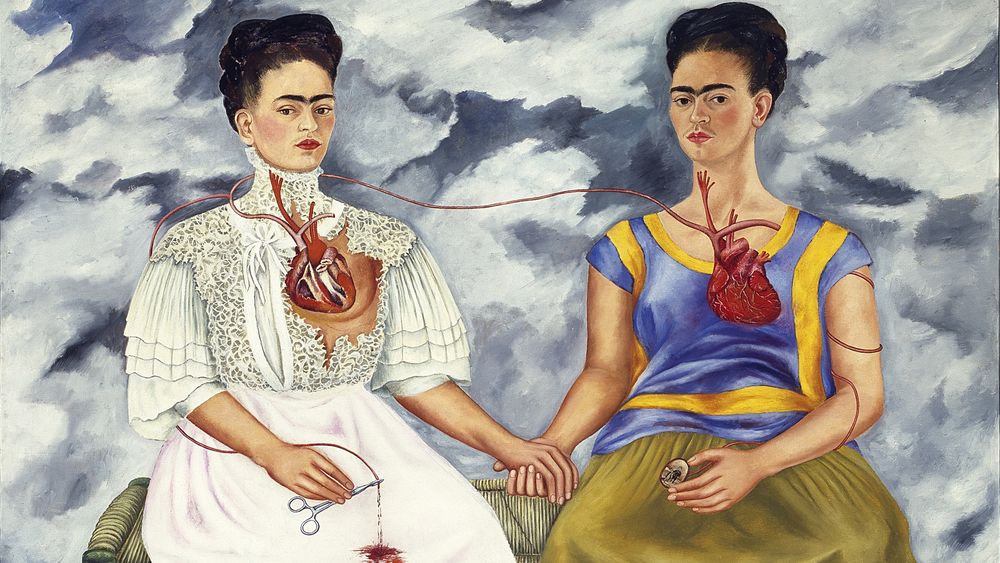

The Two Fridas and finding the balance between normalcy and reality

I thought to myself, “Twitter must have some excellent content right now, I wonder if they’ll bring back that meme of the Iraqi reporter throwing his shoes at Bush in such desperate times”, but realised that that was probably not the wisest thing to do with all of 5% battery. Well, when in doubt, there’s nothing a cup of tea can’t fix! But tea requires boiling water, and for that you need a kettle, and that also requires electricity, and by then I had finally learnt my lesson.

Obviously this was a sign from God that what I really needed to do was just *sit* with myself, whatever that superfluous saying even meant. 8 minutes had barely passed and I felt uncomfortable, restless, and really uneasy; which I found to be incredibly ironic because if this pandemic has forced us to do anything, it was to really just spend time with ourselves. So why was I feeling like this now if the last year had not, if anything been rearing me for this moment?

As soon as the first lockdown hit, we were told that with the beauties of modern-day technology, staying connected was easier than ever. Let’s be real, could the racists have really boycotted Sainsbury’s at Christmas without the community building block that is Twitter? Don’t get me wrong, this was a lifeline for many people, and personally I am genuinely grateful for that. Yet, this meant that we weren’t really alone, and in the battle of virtual company vs. physical reality, my mind had been focused on my changing relations between the company of others rather than the company of myself.

Given that not much has been happening, I, as I’m sure is the case for many other people, have personally changed a tremendous amount. And now that I had finally actively recognised that, my mind played catch-up and was looking at how one change or addition of character had affected the rest of my personality and general life outlook. It’s a beautiful point of reflection and potential reminder of how disconnected I had been with myself while I had paradoxically been stuck alone. And much like we have been trying to find alternative ways of connecting with others, the same must happen between ourselves.

So how should we go about doing that? Honestly, I’m not sure and believe it depends from person to person. Recognising it is probably the first thing, so if you’re reading this article I hope you are doing that. Instead, I’d like to use The Two Fridas by no other than Kahlo herself as a case study for how one person grappled within her disconnected and counter selves. This piece is ultimately one of self-reflection at a critical point in her life since it was created in 1939, just after Diego Rivera (fellow artist and husband at the time), asked her for a divorce. Notably, this piece does not focus on him or their relationship solely. It is a true introspection of Kahlo and her own development.

As the title gives away, we have two Fridas sitting next to each other holding hands. The Kahlo on the right is dressed in a traditional colourful Tehuana skirt and blouse, while the Kahlo to the left wears a European style wedding dress. Many people believe that this dichotomy is linked to her dual nationality as her father was German while her mother was Mexican. Critics believe that the Tehuana Kahlo was the one that Diego adored, hence why his picture is in her hands, while the European Kahlo was rejected by him. This demonstrates why there are forceps in this Kahlo’s hand which cut the blood vessel linking the two hearts. Maybe this is symbolic of her heartbreak from the loss of her love, maybe it demonstrates the countless surgeries she had to undergo in her life, or maybe it is representative of the Aztec tradition where a bleeding heart symbolises sacrifice. And if that is the case, what is she sacrificing? The answer to this question I believe is multifaceted where one interpretation does not mean that another is wrong. It is a piece inspired by a big change in her life, but rather than focusing on that one thing, it’s an analysis of how the rest of her personality is being influenced by this, or vice versa.

Kahlo herself described this portrait as a memory of childhood imaginary friends. While this may seem astray from the other interpretations we have looked at, what I like about this is that Kahlo is challenging us to think about how imaginary friends are drawn from fragments of our own minds, and in essence are therefore alternative versions of ourselves. In this piece, Kahlo is no longer a child, so she is taking that seemingly childish concept of imaginary friends and showing us how parts of her personality which may be at odds with one another may still coexist in the same person, and how establishing a relationship between all of these characteristics is a fine balancing act.

While this may be considered a surrealist piece, Kahlo rejected this idea as she believed that she painted her own reality. It is often very easy to make reality and what is normal synonyms. As I sat there in the midst of a power cut 2 months into lockdown number 2 (or 3?, I honestly do not know anymore), this notion had never felt so bogus. If this pandemic has taught us anything, it is that reality is extremely malleable, and as external circumstances change we must be aware of how we are changing with that.

The Two Fridas is also our Recreate Art piece for this month, so feel free to submit a recreation in any art medium by 5th March!

Manvir Dobb, Arts and Culture Editor

cover image via Muriel

Leave a Comment