I recently read Gender Rebels: 50 Influential Cross-Dressers, Impersonators, Name-Changers, and Game-Changers (hereafter Gender Rebels) by Anneka Harry (published 1 June 2020) and I have some thoughts about it. I’d like to start this review with a star rating, but I actually think this book defies rating for me. On balance I think I would have to give it 2.5/5 stars, but that feels both unhelpful and unrepresentative of my actual thoughts. It suggests I thought it was a completely mediocre read when actually I have feelings at both extremes…

I read a (new) feminist book and I have thoughts

The tagline of Gender Rebels reads, ‘Meet the unsung sheroes of history: the diverse, defiant and daring (wo)men who changed the rules, and their identities, to get sh*t done.’ It devotes a chapter to each of the 50 individuals featured, giving a brief overview of their lives with commentary from the author. It features people who lived throughout history, from 1507 BC right up to present day. I absolutely love the concept of the book and was so excited to read it. The concept is really the ‘5 star’ element for me as well as the fact the author has clearly done her research. Harry describes 50 different lives and experiences, although that does mean the reader only gets to spend a short chapter with each.

If I’m being completely honest, biographies of people I’ve never heard of and history books in general, fiction or non-fiction, are not something I would generally reach for. This is actually why I fall right into Gender Rebels’ target audience. It’s written by a comedian in an extremely conversational tone (more on that below) and the brevity of each overview made for quick reading that I never found boring.

The first thing I have to discuss is the aforementioned conversational tone. The book opens with an introduction from the author written in an obvious attempt to be comical which was appreciated as a way to ease the reader in to reading about history and show that Harry was trying to make it accessible to every reader. I initially thought the purpose of this writing style was to differentiate the author voice from the author’s voice – a quick, funny note from Anneka Harry as herself before launching into the main, straightforwardly-written body. Unfortunately, as soon as I turned to the first chapter I discovered this style of writing was to continue throughout. It becomes very grating very quickly with constant shoehorned-in jokes, made-up words and cultural references. However, I found that if you read a lot of it in a concentrated period, you kind of stop noticing it and it is very readable. Thankfully the style stopped being quite so much like that towards the end of the book when talking about the individuals who are still alive and including long quotes from them.

Harry is a comedian and I think the problem with the writing style boils down to her trying too hard to be funny. It reads like she’s trying to be cool and a bit irreverent and is the kind of book that, if someone didn’t like this style of writing, they might recommend for teenagers. But, to put it frankly, some of the references are very-not-young so I don’t actually think that’s what she was going for. Instead, I’d say it’s a book for people who want a quick overview of an element of history without committing to what we might consider a standard history book. A reader could dip into the book one chapter at a time or just flick to a story that interests them and read it like blog instalments. There’s no need to worry about reading it out of order or leaving it for a long time and losing the thread as all the chapters are standalone.

I’m trying not to be too scathing in the review because I didn’t not enjoy reading it. And I definitely learnt a bit about a lot of historical – and more recent – figures whom I had never heard of before and wouldn’t have otherwise. I also definitely wouldn’t have picked it up if it was a slow, dry academic book. Although I will say there is a happy middle somewhere between dry academic writing and the other extreme which is definitely where Gender Rebels lies. That being said, I flew through the book taking in some new information and appreciating some of the jokes.

Beyond the writing style, I do have some more criticisms.

It is quite superficial. The chapters are all story- and joke-telling and contain no analysis. There is no deep-dive into any time period, theme or individual. But I suppose that is fulfilling the book’s remit; when you have to cover 50 individuals in a fairly short book, there isn’t much room for anything else.

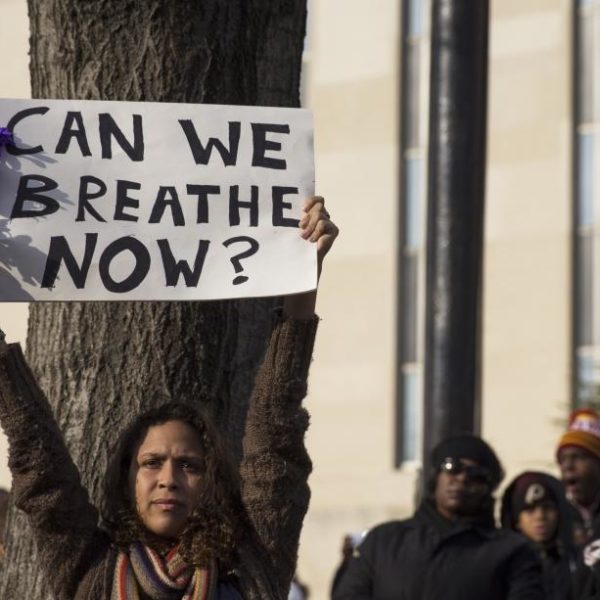

What I did think was notably missing was any analysis or critique of the structures and systems that required women to pretend to be men. Every chapter was very much ‘she could only do [X] if she cut her hair and dressed in men’s clothes because duh’ (not a real quote, but might as well be). I think just a bit more would have been appreciated at points.

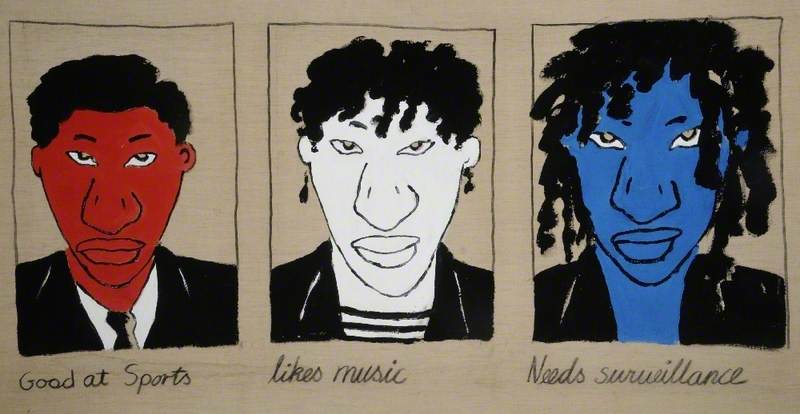

There was also no nuance at all in the way each Gender Rebel is presented. Each are written as essentially boss lady feminist icons or, as the tagline calls them, ‘sheroes’. Yes, they defied expectations and oppressive rules of the day, but some of them did some more than questionable things – including killers, pirates and thieves – that are all presented positively. A particularly notable example of a lack of nuance is when one chapter closes by talking about how the Gender Rebel ‘[fought] the good fight’ the sentence immediately after completely glossing over the fact that ‘he had a black slave.’

Of the 50 Gender Rebels mentioned, the majority are white. I suspect this is probably a result of what was available in the author’s research, but I felt it couldn’t go unmentioned as it is very hard not to notice when reading.

Towards the end of one chapter – after recounting a woman’s life story – Harry says, ‘upon coming to the end of my research I found her to have once said, “I absolutely prohibit any biography of me. My life is my own and I leave that to nobody.”’ It seems incongruous for the attitude of the whole book to be supportive of women’s autonomy, celebrating them living their lives as they chose and on their own terms, while also blatantly going against the wishes of one of the featured women by writing a biography of her.

I also have some thoughts on how the author represented the trans men that she included. Firstly, in all cases the chapters about trans individuals are titled with their birth names which goes against general practice of referring to trans people by their chosen names.

I also found her approach to pronoun usage questionable. The first instance of this is in the chapter about an individual who, later in life, went by the name Eleno, but was born Elena. Harry first describes Eleno as a female dressed as a male in order to get jobs, then she says Eleno identified as intersex, then finally as male. It isn’t until she says Eleno started to identify as male that she says she will be referring to him with male pronouns going forward. Until that point she had been using female pronouns. Given that she acknowledges that he was a man as that was how he ultimately identified, I think it might have been a better choice to start the chapter with something like, ‘Eleno was assigned female at birth and given the name Elena, but went on to identify as a man so I’ll be referring to him as ‘he’ in this chapter.’

This is an issue in common with all the trans individuals featured. Another example being when the author reveals the individual was a trans man by saying ‘pronoun change claxon’ so this is definitely a deliberate choice rather than an oversight. The choice to reveal their gender identities later in the chapters comes across as her not wanting to give ‘spoilers’ at the start of the chapter by using the appropriate pronouns as if their gender is a plot twist rather than part of their identity. Harry then goes on to say, ‘nobody knew he used to be [a lady] and had elected the life of [a gentleman]’ which seems misplaced in the context of someone who, as she is acknowledging by later specifically describing as ‘trans’, was a man. Surely the description of someone choosing the life of a gentleman would better apply to one of the many other female-identifying individuals (who chose a man’s life to gain opportunities) than someone who is not ‘choosing’ the life of a man, but rather living the way that feels most authentic.

The book is about Gender Rebels, the title makes no mention of specifically AFAB (assigned female at birth) people and the tagline includes the word ‘(wo)men’, but there is no mention at all of any trans women. It would have been nice to see some acknowledgement of trans women who have had to live their lives mostly presenting as male even though they felt female. Women having to present as men to be allowed to live their lives is literally the concept of the book and it feels like something is missing by not including these experiences.

I have no idea how any of the decisions were taken in any stage of the production of this book nor who was involved (other than the author), but I’d like to know if any trans people were involved or consulted. It definitely at no point reads like the author is intentionally not making the best choices; it just seems as though some may not have been completely thought through. An audiobook version of Gender Rebels has been recorded featuring the voices of some famous women so I imagine the book is expected to do very well. Ultimately, I’m glad a book like this exists – I just wish it existed differently.

Leave a Comment